Occasionally Alán Aspuru-Guzik has a movie-star moment, when fans half his age will stop him in the street. “They say, ‘Hey, we know who you are,’” he laughs. “Then they tell me that they also have a quantum start-up and would love to talk to me about it.” He doesn’t mind a bit. “I don’t usually have time to talk, but I’m always happy to give them some tips.” That affable approach is not uncommon in the quantum-computing community, says Aspuru-Guzik, who is a computer scientist at the University of Toronto and co-founder of Zapata Computing in Cambridge, Mass. Although grand claims have been made about a looming revolution in computing, and private investment has been flowing into quantum technology, it is still early days, and no one is sure whether it is even possible to build a useful quantum computer.

Today’s quantum machines have at best a few dozen quantum bits, or qubits, and they are often beset by computation-destroying noise. Researchers are still decades—and many thousands of qubits—away from general-purpose quantum computers, ones that could do long-heralded calculations such as factoring large numbers. A team at Google has reportedly demonstrated a quantum computer that can outperform conventional machines, but such “quantum supremacy” is expected to be extremely limited. For general applications, 30 years is “not an unrealistic timescale,” says physicist John Preskill of the California Institute of Technology. Some researchers have raised the possibility that, if quantum computers fail to deliver anything of use soon, a quantum winter will descend: enthusiasm will wane and funding will dry up before researchers get anywhere close to building full-scale machines. “Quantum winter is a real concern,” Preskill says. Yet he remains upbeat because the slow progress has forced researchers to adjust their focus and see whether the devices they have already built might be able to do something interesting in the near future.

Judging from a flurry of papers published during the past few years, it’s a definite possibility. This is the era of the small, error-prone, or “noisy intermediate-scale quantum” (NISQ), machine, as Preskill has put it. And so far it has turned out to be a much more interesting time than anyone had anticipated. Although the results are still quite preliminary, algorithm designers are finding work for NISQ machines that could have an immediate impact in chemistry, machine learning, materials science and cryptography—offering insights into the creation of chemical catalysts, for example. These innovations are also provoking unexpected progress in conventional computing. All this activity is running alongside efforts to build bigger, more robust quantum systems. Aspuru-Guzik advises people to expect the unexpected. “We’re here for the long run,” he says. “But there might be some surprises tomorrow.”

Fresh Prospects

Quantum computing might feel like a 21st-century idea, but it came to life the same year that IBM released its first personal computer. In a 1981 lecture, physicist Richard Feynman pointed out that the best way to simulate real-world phenomena that have a quantum-mechanical basis, such as chemical reactions or the properties of semiconductors, is with a machine that follows quantum-mechanical rules. Such a computer would make use of entanglement, a phenomenon unique to quantum systems. With entanglement, a particle’s properties are affected by what happens to other particles with which it shares intimate quantum connections. These links give chemistry and many branches of materials science a complexity that defies simulation on classical computers. Algorithms designed to run on quantum computers aim to make a virtue of these correlations, performing computational tasks that are impossible on conventional machines.

Yet the same property that gives quantum computers such promise also makes them difficult to operate. Noise in the environment, whether from temperature fluctuations, mechanical vibrations or stray electromagnetic fields, weakens the correlations among qubits, the computational units that encode and process information in the computer. That degrades the reliability of the machines, limits their size and compromises the kinds of computation that they can perform. One potential way to address the issue is to run error-correction routines. Such algorithms, however, require their own qubits—the theoretical minimum is five error-correcting qubits for every qubit devoted to computation—adding a lot of overhead costs and further limiting the size of quantum systems.

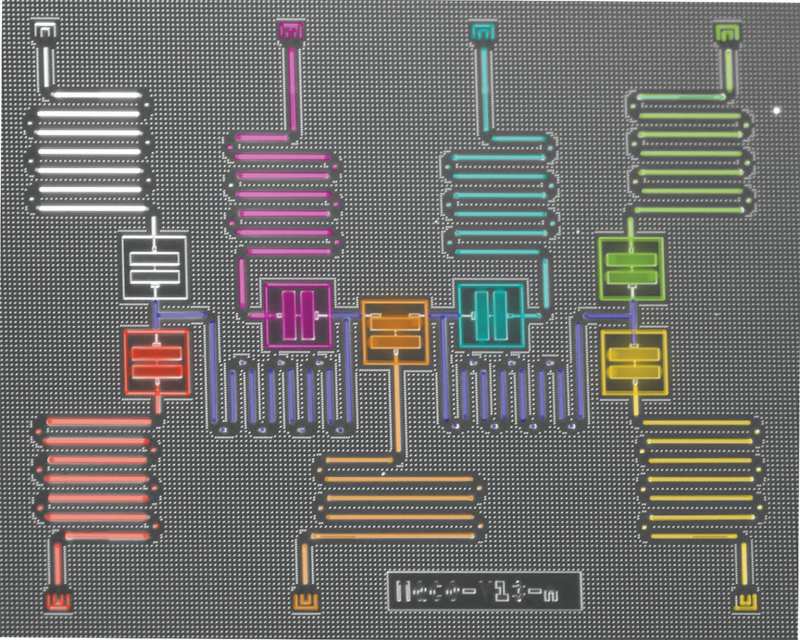

Some researchers are focusing on hardware. Microsoft Quantum’s multinational team is attempting to use exotic “topological particles” in extremely thin semiconductors to construct qubits that are much more robust than today’s quantum systems. But these workarounds are longer-term projects, and many researchers are focusing on what can be done with the noisy small-scale machines that are available now—or will be in the next five to 10 years. Instead of aiming for a universal, error-corrected quantum computer, for example, physicist Jian-Wei Pan and his team at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei are pursuing short- and mid-term targets. That includes quantum supremacy and developing quantum-based simulators that can solve meaningful problems in areas such as materials science. “I usually refer to it as ‘laying eggs along the way,’” he says.

Bert de Jong of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory has his eye on applications in chemistry, such as finding alternatives to the Haber process for the manufacture of ammonia. At the moment, researchers must make approximations to run their simulations on classical machines, but that approach has its limits. “To enable large scientific advances in battery research or any scientific area relying on strong electron correlation,” he says, “we cannot use the approximate methods.” NISQ systems won’t be able to perform full-scale chemistry simulations. But when combined with conventional computers, they might demonstrate an advantage over existing classical simulations. “The classically hard part of the simulation is solved on a quantum processor, while the rest of the work is done on a classical computer,” de Jong says.

This kind of hybrid approach is where Aspuru-Guzik earned his fame. In 2014 he and his colleagues devised an algorithm called the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE), which uses conventional machines to optimize guesses. Those guesses might be about the shortest path for a traveling salesperson, the best shape for an aircraft wing or the arrangement of atoms that constitutes the lowest energy state of a particular molecule. Once that best guess has been identified, the quantum machine searches through the nearby options. Its results are fed back to the classical machine, and the process continues until the optimum solution is found. As one of the first ways to use NISQ machines, VQE had an immediate impact, and teams have used it on several quantum computers to find molecular ground states and explore the magnetic properties of materials.

That same year Edward Farhi, then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, proposed another heuristic, or best-guess, approach called the quantum approximation optimization algorithm (QAOA). The QAOA, another quantum-classical hybrid, performs what is effectively a game of quantum educated guessing. The only application so far has been fairly obscure—optimizing a process for dividing up graphs—but the approach has already generated some promising spin-offs, says Eric Anschuetz, a graduate student at M.I.T., who has worked at Zapata. One of those, devised by Anschuetz and his colleagues, is an algorithm called variational quantum factoring (VQF), which aims to bring the encryption-breaking, large-number-factoring capabilities of quantum processing to NISQ-era machines.

Until VQF, the only known quantum algorithm for such work was one called Shor’s algorithm. That approach offers a fast route to factoring large numbers but is likely to require hundreds of thousands of qubits to go beyond what is possible on classical machines. In a paper published in 2019, Zapata researchers suggest that VQF might be able to outperform Shor’s algorithm on smaller systems within a decade. Even so, no one expects VQF to beat a classical machine in that time frame. Others are looking for more general ways to make the most of NISQ hardware. Instead of diverting qubits to correct noise-induced errors, for example, some scientists have devised a way to work with the noise. With “error mitigation,” the same routine is run on a noisy processor multiple times. By comparing the results of runs of different lengths, researchers can learn the systematic effect of noise on the computation and estimate what the result would be without noise.

The approach looks particularly promising for chemistry. In March 2019 a team led by physicist Jay Gambetta of IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., showed that error mitigation can improve chemistry computations performed on a four-qubit computer. The team used the approach to calculate basic properties of the molecules hydrogen and lithium hydride, such as how their energy states vary with interatomic distance. Although single, noisy runs did not map onto the known solution, the error-mitigated result matched it almost exactly.

Errors might not even be a problem for some applications. Vedran Dunjko, a computer scientist and physicist at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, notes that the kinds of tasks performed in machine learning, such as labeling images, can cope with noise and approximations. “If you’re classifying an image to say whether it is a human face, or a cat, or a dog, there is no clean mathematical description of what these things look like—and nor do we look for one,” he says.

Fuzzy Future

Gambetta’s team at IBM has also been pursuing quantum machine learning for NISQ systems. In early 2019, while working with researchers at the University of Oxford and at M.I.T., the group reported two quantum machine-learning algorithms that are designed to pick out features in large data sets. It is thought that as quantum systems get bigger, their data-handling capabilities should grow exponentially, ultimately allowing them to handle many more data points than classical systems can. The algorithms provide “a possible path to quantum advantage,” the team wrote.

But as with other examples in the machine-learning field, no one has yet managed to demonstrate a quantum advantage. In the era of NISQ computing, there is always a “but.” Zapata’s factoring algorithm, for instance, might never factor numbers faster than classical machines. No experiments have been done on real hardware yet, and there is no way to definitively, mathematically prove superiority.

Other doubts are arising. Gian Giacomo Guerreschi and Anne Matsuura of Intel Labs in Santa Clara, Calif., performed simulations of Farhi’s QAOA algorithms and found that real-world problems with realistically modeled noise do not fare well on machines the size of today’s NISQ systems. “Our work adds a word of caution,” Guerreschi says. “If order-of-magnitude improvements to the QAOA protocols are not introduced, it will take many hundreds of qubits to outperform what can be done on classical machines.” One general problem for NISQ computing, Dunjko points out, comes down to time.

Conventional computers can effectively operate indefinitely. A quantum system can lose its correlations, and thus its computing power, in fractions of a second. As a result, a classical computer does not have to run for very long before it can outstrip the capabilities of today’s quantum machines. NISQ research has also created a challenge for itself by focusing attention on the shortcomings of classical algorithms. It turns out that many of those, when investigated, can be improved to the point at which quantum algorithms cannot compete.

In 2016, for instance, researchers developed a quantum algorithm that could draw inferences from large data sets. It is known as a type of recommendation algorithm because of its similarity to the “you might also like” algorithms used online. Theoretical analysis suggested that this scheme was exponentially faster than any known classical algorithm. But in July 2018 computer scientist Ewin Tang, then an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, formulated a classical algorithm that worked even faster. Tang has since generalized her tactic, taking processes that make quantum algorithms fast and reconfiguring them so that they work on classical computers. This has allowed her to strip the advantage from a few other quantum algorithms, too.

Despite the thrust and parry, researchers say it is a friendly field and one that is improving both classical computing and quantum approaches. “My results have been met with a lot of enthusiasm,” says Tang, who is now a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington. For now, however, researchers must contend with the fact that there is still no proof that today’s quantum machines will yield anything of use. NISQ could simply turn out to be the name for the broad, possibly featureless landscape researchers must traverse before they can build quantum computers capable of outclassing conventional ones in helpful ways.

“Although there were a lot of ideas about what we could do with these near-term devices,” Preskill says, “nobody really knows what they are going to be good for.” De Jong, for one, is okay with the uncertainty. He sees the short-term quantum processor as more of a lab bench—a controlled experimental environment. The noise component of NISQ might even be seen as a benefit because real-world systems, such as potential molecules for use in solar cells, are also affected by their surroundings. “Exploring how a quantum system responds to its environment is crucial to obtain the understanding needed to drive new scientific discovery,” he says.

For his part, Aspuru-Guzik is confident that something significant will happen soon. As a teenager in Mexico, he used to hack phone systems to get free international calls. He says he sees the same adventurous spirit in some of the young quantum researchers he meets—especially now that they can effectively “dial in” and try things out on the small-scale quantum computers and simulators made available by companies such as Google and IBM. This ease of access, he thinks, will be key to working out the practicalities.

“You have to hack the quantum computer,” Aspuru-Guzik says. “There is a role for formalism, but there is also a role for imagination, intuition and adventure. Maybe it’s not about how many qubits we have; maybe it’s about how many hackers we have.”